The Paraguayan Chaco is a semi-arid region in Paraguay consisting of more than 60% of Paraguay's land area but with less than 2% of the population. It is known as "El Infierno Verde" (The Green Hell) by the locals due to the hot, dry and dusty environment. Despite the harsh conditions in the Chaco, an abundance of wildlife exists. It was this rich biodiversity which drew us to the Chaco. We arrived in Asunción, the capital of Paraguay, on July 26 and the following morning we were headed northwest on the Trans-Chaco Highway (National Route 9) which runs about 470 miles to the Bolivian border. We were accompanied by our guide, Rob Clay, and our driver, Francisco Rojas (Franci). The southern reaches of the Chaco are more humid and with palm trees and the occasional marsh flashing by.

We stopped at a popular empanada restaurant, Parador Pirahu, for lunch. Not far from Pirahu, we came to a line of traffic stopped in the road. At first we thought road construction had halted the flow of traffic but soon found out it was caused by a road block 3.5 miles ahead! Apparently the indigenous people in Pozo Colorado had closed the road in an attempt to convince the government to make their tiny community a municipality. We had no choice but to join the queue and hope that the road would be opened soon.

|

| Palm Trees in the Humid Chaco |

We stopped at a popular empanada restaurant, Parador Pirahu, for lunch. Not far from Pirahu, we came to a line of traffic stopped in the road. At first we thought road construction had halted the flow of traffic but soon found out it was caused by a road block 3.5 miles ahead! Apparently the indigenous people in Pozo Colorado had closed the road in an attempt to convince the government to make their tiny community a municipality. We had no choice but to join the queue and hope that the road would be opened soon.

Rumors kept coming down the line that up to 3000 protesters had amassed to make their point. After a few false rumors that the road would open in an hour we were finally on our way a mere 5 hours later! By this time it was dark and a 10-mile long line of trucks had built up over the course of the 10 hours the road had been closed. We inched our way forward to a toll both where we still had to pay (you think they would have waived the fee under the circumstances) and started to move faster. Now we had to pass the slow-moving trucks on a relatively narrow road with a lot of oncoming traffic. Finally after about an hour and a half we had cleared the line and were on our way. We didn't arrive at our destination until 11:00 PM.

We were up early the next morning to walk to Laguna Capitán. In the path about 200 feet away sat a dark animal which at first glance looked like a cross between a cat and an otter. Closer inspection with our binoculars revealed a Jaguarundi, the first we had ever seen! The Jaguarundi is a small wild cat native to Central and South America although they have been found as far north as Texas and there have been sightings in Florida. With its short legs, elongated body and long tail, this cat looked more like an otter from a distance.

When we arrived at the Laguna small flocks of Winged Teal, White-backed Stilts, Lesser Yellowlegs and a few Chilean Flamingos were swimming in the saline water. A lone Lowland Tapir popped out and ambled across the mud flats. The species is vulnerable due to poaching and habitat loss.

|

| Jaguarundi! |

When we arrived at the Laguna small flocks of Winged Teal, White-backed Stilts, Lesser Yellowlegs and a few Chilean Flamingos were swimming in the saline water. A lone Lowland Tapir popped out and ambled across the mud flats. The species is vulnerable due to poaching and habitat loss.

That evening we drove out to Laguna Salada in the hopes of seeing large flocks of flamingos and possibly some mammals but the flamingos were on the far shore and no animals showed up. On our night drive back to Laguna Capitán, mammal activity was extremely quiet. We saw only 3 animals, a Tapeti or Brazilian Rabbit, a Capybara and a Southern Tamandua. Views of the animals were brief and Marc was not able to get any photos.

The next day we continued our drive north to the Mennonite town of Lomo Plata to pick up supplies. The first Mennonites arrived in the Gran Chaco in 1927 from Canada where they had been living since the late 1800's having originally emigrated from Russia. The Paraguay government welcomed them as they established a Paraguayan presence in the then uninhabited Chaco. A second wave of Russian Mennonites arrived in 1947. Today they own vast cattle estancias or ranches in the region and sadly are deforesting large tracts of forest. The cities they have built over the years however provide vital supplies of food, petrol and water for travelers heading even further north where infrastructure is nonexistent.

|

| Ready for the Long Drive North |

From Lomo Plata we took a detour from the Trans-Chaco Highway to visit the Centro Chaqueño para la Conservación e Investigación (CCCI), a Chacoan Peccary breeding center at Fortin Toledo. To learn more about the center and how you can help go to:

The story of the Chacoan Peccary is a fascinating one. The existence of the animal was only known from fossil records and was thought to be extinct. What a shock it must have been for American zoologist Ralph Wetzel when he discovered them alive and well in Paraguay in 1972, a real life Jurassic Park story! We don't usually like to see animals in captivity but here they are bred in the hopes of releasing them into the wild. Besides it gave us a great opportunity to see a rare mammal up close and observe its behavior. The peccaries have learned that tourists will toss them pieces of opuntia cactus which we were more than happy to do. It was interesting to see how the peccaries remove the thorns by scraping the cactus on the ground with their leathery snouts.

The story of the Chacoan Peccary is a fascinating one. The existence of the animal was only known from fossil records and was thought to be extinct. What a shock it must have been for American zoologist Ralph Wetzel when he discovered them alive and well in Paraguay in 1972, a real life Jurassic Park story! We don't usually like to see animals in captivity but here they are bred in the hopes of releasing them into the wild. Besides it gave us a great opportunity to see a rare mammal up close and observe its behavior. The peccaries have learned that tourists will toss them pieces of opuntia cactus which we were more than happy to do. It was interesting to see how the peccaries remove the thorns by scraping the cactus on the ground with their leathery snouts.

|

| Chacoan Peccary Removing Thorns |

Also in the area were Chacoan Mara, a bizarre creature that looked like a cross between a rabbit and a small antelope. Could this be the legendary jackalope that we had heard about? They are the fourth largest rodent in the world and would pose nicely for us providing you didn't get too close.

That night we did a drive in the area with spotlights looking for mammals. We encountered only three: a Crab-eating Raccoon, a Pampas Fox and a distant view of a Geoffroy's Cat. Again it was difficult photographing the animals as they were quite wary and didn't stick around for very long. The Chaco Owls restricted to the dry Chaco were much more obliging in having their photo taken.

The next morning we again visited the captive peccaries when I noticed something odd. Two Chacoan Peccaries were outside the fence! Marc had seen a peccary cross the trail but we assumed it was a more common Collared Peccary. We asked a worker at the center if two of their Chacoan Peccaries had escaped and he said all were accounted for. These could only be wild Chacoan Peccaries!

We continued our journey north to the town of Mariscal Estigarribia, one of the last outposts of civilization where we filled up with diesel and picked up more water and ice. The road which had been paved up to this point became riddled with crater-sized potholes. They were too deep to cruise over and too big to drive around so we had to drive slowly into them and crawl out the other side. Travel at this speed did allow Franci to spot a Conover's Tuco-Tuco on the road! Rob jumped out and grabbed the animal before it could escape into its burrow. These subterranean rodents are rarely above ground and we didn't want to miss the opportunity to get a good look at it.

We arrived at our next destination, Teniente Encisco National Park, around dusk and checked into our accommodation at the park headquarters. Early the next morning we explored the road by foot. Chacoan Maras scurried across our path but never let us approach too closely. We drove down the road a bit further to see if we could find more mammals but only a lone Pampas Fox came trotting up the road but veered off as soon as he saw our vehicle.

Bizarre-looking Bottle trees (Ceiba chodatii) were common in the dry Gran Chaco. They have a bottle-shaped swollen trunk in which to store water for the dry season.

That afternoon we made the 40-mile drive up to Médanos del Chaco National Park to look for more wildlife. Surprisingly we encountered only one mammal on our long drive, a Southern Three-banded Armadillo. Rob caught him for us so we could get a close look. They are they only armadillo species that can completely curl itself into a ball as a defense mechanism.

|

| Pampas Fox |

Bizarre-looking Bottle trees (Ceiba chodatii) were common in the dry Gran Chaco. They have a bottle-shaped swollen trunk in which to store water for the dry season.

|

| Bottle Tree |

That afternoon we made the 40-mile drive up to Médanos del Chaco National Park to look for more wildlife. Surprisingly we encountered only one mammal on our long drive, a Southern Three-banded Armadillo. Rob caught him for us so we could get a close look. They are they only armadillo species that can completely curl itself into a ball as a defense mechanism.

We made the return drive back to Teniente Enciso after dark hoping to see nocturnal mammals along the way but not one animal crossed our path until we neared the park headquarters. Marc spotted a Plains Viscacha on the side of the road and a second shot across the road too quickly for a photo. After an unproductive drive the following morning we decided to leave Teniente Enciso a day early and returned to Mariscal Estigarribia where we checked into the Airport Hotel! Yes, in this tiny outpost in the middle of nowhere there was actually an airport and a hotel! Mystery still surrounds who built the airport and for what reason. The concrete runway is wider than the one in Asunción and according to one source is wide enough for a B-52. The US government contends that the airport was built by the Paraguayan government between 1977 and 1986 to create a free trade zone. Claims surfaced in 2005 that the US planned on using the airport as a military base which the US government denied. The truth may never be known.

The following morning we left Mariscal Estigarribia and headed toward the northeast to Defensores del Chaco National Park. Tourist infrastructure is limited here and we opted to camp at Cerro Leon. We took a short walk to a mirador or lookout for views over the Gran Chaco. When we returned to camp Franci said there were monkeys in the tree above our tents. They had moved off but we spotted them in a nearby tree and confirmed that they were Azara's Night Monkeys.

The following morning we were up early to climb to the top of a higher mirador to watch the sun rise. We looked out over the unbroken forest of the Gran Chaco and could only imagine what undiscovered creatures dwelled in the unpenetrable forest. Rob told us some of the last uncontacted tribes in South America still survive in this unforgiving landscape.

|

| Sunrise Over the Gran Chaco |

Back at camp we could hear two groups of Chacoan Titi Monkeys calling to each other across the road but we could not spot them in the dense vegetation. Lucky for us a small group was foraging in a bare tree next to the road. They moved off at our approach and hid in a tall cactus tree. I can't say I've ever seen monkeys in a cactus before.

|

| Chacoan Titi Monkey |

We weren't seeing many mammals in this part of Defensores possibly because it was very dry so we decided to move to Madrejon, a section of the park with more water. On our first night drive in this area we encountered 6 Crab-eating foxes, more than we had seen on the entire trip up to this point. They were drawn to tiny pools where frogs abounded and yes, there were crabs.

|

| Crab-eating Fox |

Right across from the rangers' station where we were staying was another one of these ponds. We caught the eyeshine of a feline slinking in the grass. We thought it was a Geoffroy's Cat, the species most likely encountered in the dry Chaco but when we looked at Marc's photos we weren't so sure. I posted a photo on Mammal Watching's Facebook page for help with identification and it turned out the cat was an ocelot!

The daytime sightings here were also a bit better. We encountered a lone Chacoan Peccary ambling down the road. We stopped to let him approach us but as we were waiting we could see a pickup truck barreling down the road in the opposite direction.

|

| Chacoan Peccary in the Road |

Fortunately the peccary got off the road in time but many other animals are not so lucky. In fact we saw a recently killed Crab-eating Fox on the road shortly after. This is just another example of how ranching in the area is adversely effecting the wildlife.

On August 5 we began the long drive back to Asunción stopping at Fortin Toledo again to spend the night. We visited the captive peccaries one last time and as we were leaving caught another wild Chacoan Peccary visiting the enclosures. This was our 6th wild individual sighting and Rob commented that we were very fortunate to get so many close encounters with these "living fossils".

We spent the night in Asunción before heading east the following morning. We were on our way to visit another highly threatened biome in Paraguay, the Atlantic Forest. Only a small island remains, protected in the Mbaracayu Forest Reserve. The reserve was originally purchased by The Nature Conservancy but is now run by the Moises Bertoni Foundation. To learn more about the reserve and how you can help go to:

When we arrived we were greeted by one of the friendly young women who run the lodge within the reserve. We headed out in the afternoon to explore the reserve and as we were driving back after dark, startled a Crab-eating Fox on the road. We pushed him into the territory of a second male and a nasty fight ensued with lots of snarling and yelping. A third fox most likely a female trotted off with the victor.

We spent the night in Asunción before heading east the following morning. We were on our way to visit another highly threatened biome in Paraguay, the Atlantic Forest. Only a small island remains, protected in the Mbaracayu Forest Reserve. The reserve was originally purchased by The Nature Conservancy but is now run by the Moises Bertoni Foundation. To learn more about the reserve and how you can help go to:

When we arrived we were greeted by one of the friendly young women who run the lodge within the reserve. We headed out in the afternoon to explore the reserve and as we were driving back after dark, startled a Crab-eating Fox on the road. We pushed him into the territory of a second male and a nasty fight ensued with lots of snarling and yelping. A third fox most likely a female trotted off with the victor.

|

| Crab-eating Fox Fight! |

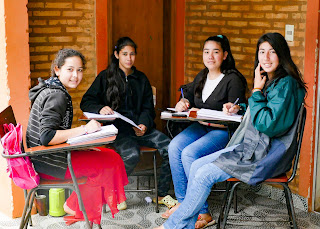

The next day we awoke to rain which cut our morning walk short. We were given a presentation about the reserve by one of the young woman and learned that a novel model in conservation and community development is in the works here. Not only is the forest protected but there is a school here which boards 120 mostly local women working on their high school degrees. Only women are admitted in an effort to give them opportunities they normally would not have access to. The students participate in a combination of field work and classroom studies and run the ecotourism side of the reserve. It's an approach that's working. The local community has embraced the reserve because it provides an education for their daughters.

|

| Students at Mbaracayu Forest Reserve School |

That afternoon we braved the rain and mud and attempted to cross the reserve. We couldn't believe the transition from the dry, dusty Chaco to the wet and lush Atlantic Forest. The two areas were only 200 miles apart. The road had become flooded and as we were crossing a particularly wet section, our front left wheel dropped into a deep hole with a loud crunch and our vehicle came to an abrupt stop. Franci got out to access the damage and the look of dismay on his face said it all. The front wheel had broken off and lay on the muddy ground!

It was still pouring so we stayed in the car while Franci took the wheel apart to see if by some miracle he could fix it. To our utter amazement all 5 bolts holding the wheel in place had been sheared off but no other damage had been done! Now all Franci had to do was to come up with spare bolts. Rob hung out in the pouring rain to provide moral support and plenty of hot mate. After removing the front bumper and a bolt from the right wheel, Franci had enough bolts to put the left wheel back on. What an ingenious mechanic he is! He made all the repairs in the cold rain and from inside the warm and dry vehicle we could hear him chuckling with Rob. Our vehicle looked a bit pathetic but it would get us back the 7 miles to the reserve headquarters!

|

| Our Wounded Vehicle |

The rain had stopped and we were greeted with sunny skies the next morning just in time for our return to Asunción. We stopped at Arroyos Y Esteros on the way back where I finally saw a Brazilian Cavy or Guinea Pig. The sun was setting over the marsh lighting up the brilliant color of a Scarlet-headed Blackbird.

It was time to return to Asunción to catch an early morning flight home tomorrow. Although not the mammal watching extravaganza we had hoped for, our 2-week visit turned out to be quite the adventure. We had seen a lot of the country, covering a whopping 2400 miles! We had great encounters with Chacoan Peccaries, the animal I had most wanted to see and learned a lot about the conservation issues facing Paraguay. A heartfelt thanks goes to our guide Rob who taught us so much about the birds and animals of the Chaco and the threats they face. We are extremely grateful for Franci's ability to drive long distances and to fix all our mechanical problems and he was a good cook to boot!

We hope all is well back home.

Peggy and Marc

Our mammal list:

| No. | Species | Scientific Name | Notes |

| 1 |

Ocelot

|

Leopardus pardalis

|

One at Defensores Del Chaco (Madrejon), at night.

|

| 2 |

Geoffroy's Cat

|

Leopardus geoffroi

|

One at Fortin Toledo at distance at night and the other at Defensores del Chaco (Madrejon) seen by Marc.

|

| 3 |

Jaguarundi

|

Puma yagouaroundi

|

Two individuals, one at Laguna Capitan and the other crossing the road at Defensores del Chaco (Madrejon)

|

| 4 |

Pampas Fox

|

Pseudalopex gymnocercus

|

Only four individuals on night drives in the Gran Chaco.

|

| 5 |

Crab-eating Fox

|

Cerdocyon thous

|

Common at Madrejon and 3 individuals at Mbaracayu Forest Reserve

|

| 6 |

Molina's Hog-nosed Shunk

|

Conepatus chinga

|

One at night along the road at Fortin Toledo.

|

| 7 |

Crab-eating Raccoon

|

Procyon cancrivorus

|

Two at night along he road at Fortin Toledo.

|

| 8 |

Southern Tamandua

|

Tamandua tetradactyla

|

One at night along the road at Laguna Capitan.

|

| 9 |

Lowland Tapir

|

Tapirus terrestris

|

Two individuals, one at Laguna Capitan and one at Defensores del Chaco Madrejon).

|

| 10 |

Grey Brocket Deer

|

Mazama gouazoubira

|

One seen on a walk at Fortin Toledo.

|

| 11 |

Chacoan Peccary

|

Catagonus wagneri

|

Six individuals, 3 visiting captive peccaries at Fortin Toledo, 2 at Teniente Enciso and one at Defensores del Chaco (Madrejon).

|

| 12 |

Azara's Night Monkey

|

Aotus azarae

|

Group of three at Defensores del Chaco (Cerro Leon)

|

| 13 |

Chacoan Titi Monkey

|

Callicebus pallescens

|

Group of three at Defensores del Chaco (Cerro Leon)

|

| 14 |

Southern Three-banded Armadillo

|

Tolypeutius matacus

|

Two individuals, one on the road between Teniente Enciso Medanos del Chaco during the day and one at night at Fortin Toledo.

|

| 15 |

Tapeti

|

Sylvilagus brasiliensis

|

3 individuals, one near Laguna Salada, one at Cerro Leon, one at Madrejon

|

| 16 |

Capybara

|

Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris

|

2 individuals, one near Laguna Salada, one near Mariscal Estigarriba

|

| 17 |

Plains Viscacha

|

Lagostomus maximus

|

2 individuals at Teniente Enciso

|

| 18 |

Chacoan Mara

|

Dolichotis salinicola

|

Several at Fortin Toledo and Teniente Enciso

|

| 19 |

Conover's Tocu-tocu

|

Ctenomys conoveri

|

One on the road from Mariscal Estigarriba to Teniente Enciso

|

| 20 |

Brazilian Guinea Pig

|

Cavia aperea

|

One on the road from south of Pirahu and two at Arroyos Y Esteros

|

| 21 |

Lessor Grison

|

Galictis cuja

|

One running across the road to Asuncion south of Pirahu

|

| 22 |

Azara's Agouti

|

Dasyprocta azarae

|

Two in Mbaracayu Forest Reserve

|